Tribute to Bernard Citroen

Written by Bernard’s great-grandson, Jacques Edson Citroen Hymans, for the unveiling ceremony of the Struikelsteen in his honor at Spruitenbosstraat 5, Haarlem, the Netherlands, on January 29, 2026

Bernard Jacob Citroen was born in Amsterdam in 1865, the first of eleven children of Jacob and Mathilde Citroen.

Bernard’s father, Jacob Citroen, was the founder of the Nederlandse Gouden Kettingen-fabriek (“Dutch Gold Chain Factory”), located at Sarphatistraat 103 in Amsterdam. The archives of the pioneering 1898 Nationale Tentoonstelling van Vrouwenarbeid (“National Exhibition of Women’s Labor”) hold a letter from Jacob that was displayed at the exhibition, in which he explained that his quest for advantage over his competitors had led him start hiring women workers, who in his opinion “alleen de geschiktheid bleken te bezitten voor een werk, waarvoor het uiterste geduld en vaardigheid vereist wordt, wat bij geen mannelijk person te vinden is” (“alone proved to possess the aptitude for work that required the utmost patience and skill—qualities not found in men”). He continued, “Er nu in 20 tal in de fabriek werkzaam zijn, waarbij zelf eene sedert 1841, welke eene goede gezondheid geniet, dus wel een bewijs, dat het werk geene nadelige gevolgen heeft of het gestel der vrouw.” (“At present, around twenty girls are employed in the factory, one of whom has been there since 1871 and still enjoys good health. This is clear proof that the work has no harmful effect on the constitution of women.”)

Bernard ran the business after his father’s death in 1910. According to family lore, it failed around the end of that decade due to the sudden popularity of the wristwatch, which greatly depressed consumer demand for pocketwatches and their accompanying gold chains.

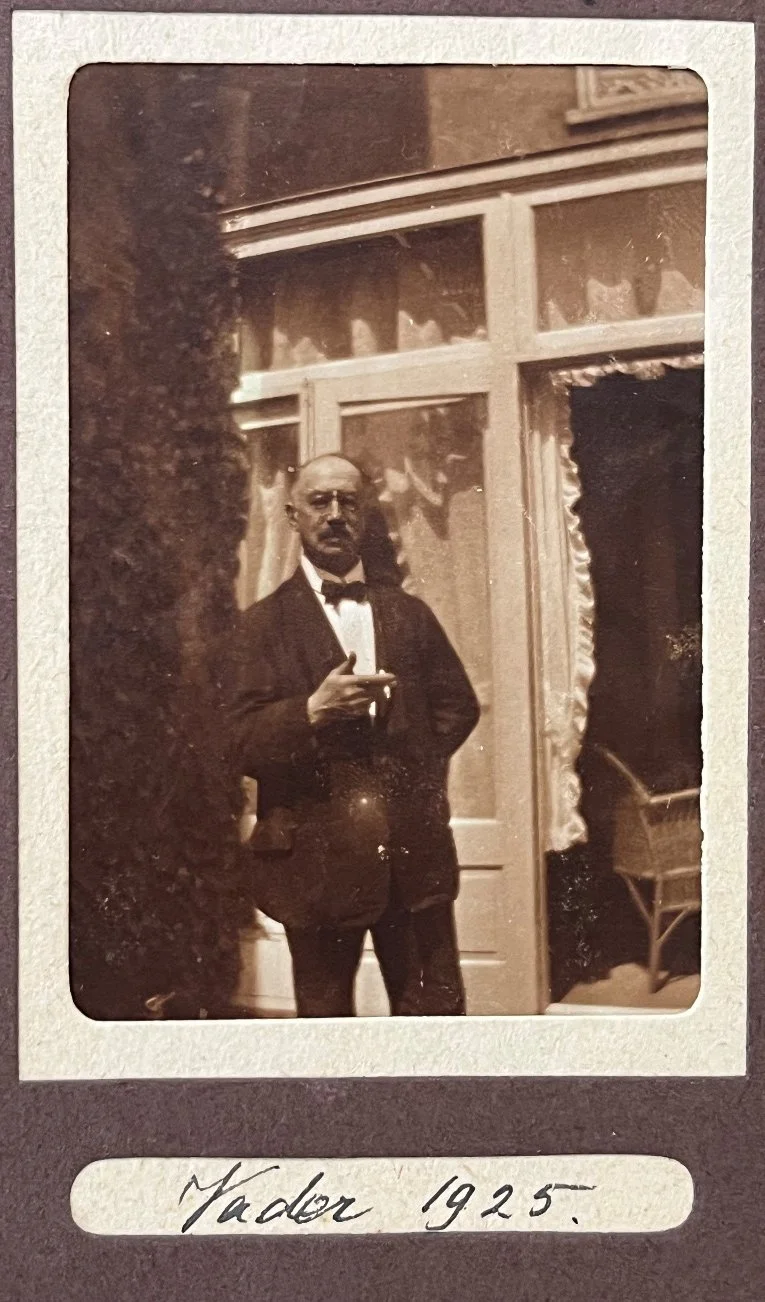

Around the same time, Bernard, his wife Emma and their only child Johanna (“Hanna”) moved to Spruitenboschstraat 5 in Haarlem. Here is a picture of him from 1925, mostly likely taken by Hanna at their home.

Having inherited his father’s belief in women’s aptitude for work, Bernard strongly encouraged his daughter’s academic ambitions. Hanna graduated from high school in Haarlem in 1924 and then studied at the University of Amsterdam, including a stint as a visiting student at the University of Uppsala, Sweden. In 1931, she earned a master’s degree for her studies in German, Swedish, and Old French. She then pursued doctoral studies until March 1934, when she married Jacques Herman Hijmans of Rotterdam. Jacques was a manager and part-owner of his family’s business, the large Rotterdam-based textile firm Herman Hijmans & Co.

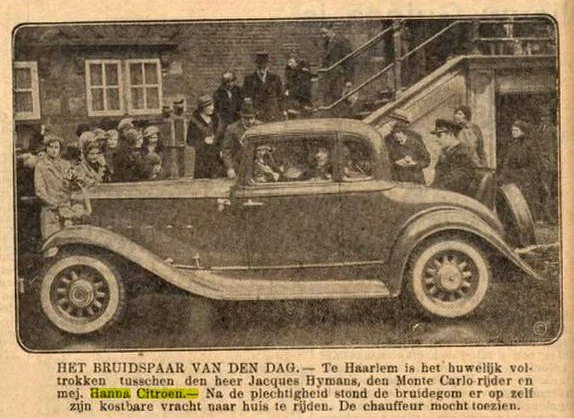

The picture below depicts Hanna and Jacques in front of the Citroen family home at Spruitenboschstraat 5 on their wedding day.

Vertrek uit het “ouderlijk” huis Spruitenboschstraat 5 te Haarlem ‘s morgens 11 uur.

Hanna and Jacques were wed in a Jewish ceremony in Haarlem and registered their marriage at Haarlem city hall. Dutch newspapers as far away as the Dutch East Indies’ Sumatra Post carried a photograph of the newlyweds in a luxury automobile in front of the city hall, surrounded by family and friends.

A comical wedding-day “newspaper” that was probably written mostly by Bernard poked fun at the various members of the wedding party. One of the “advertisements” in its “classifieds” section was for the “Patisserie Bernard. Dagelykse versche moppen verkrygbar” (“Fresh jokes available daily”).

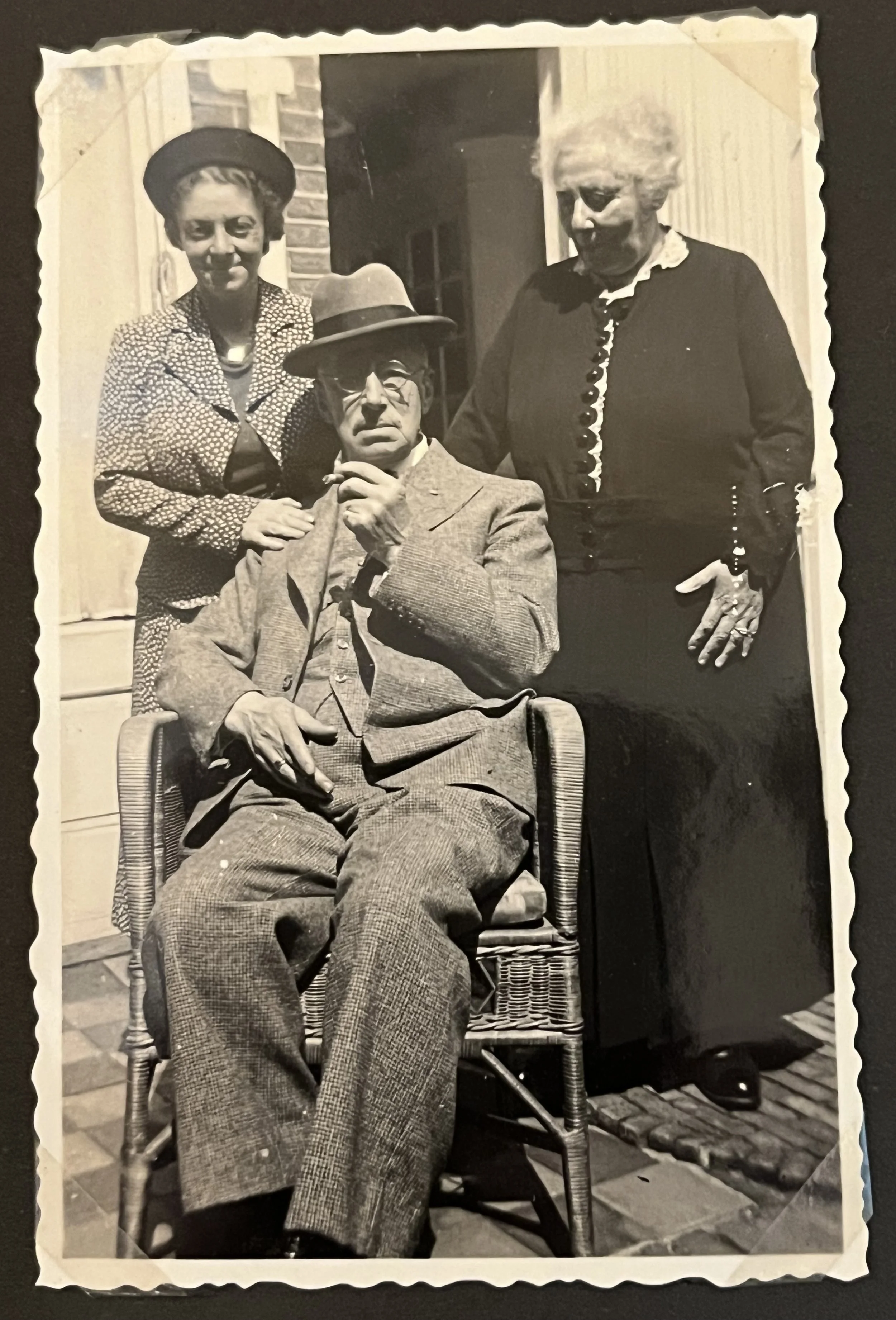

After her marriage, Hanna moved to Rotterdam but often returned home to visit her parents. Here is a picture from one of those visits in 1934 or 1935.

Bernard’s wife Emma died in 1936. In 1939, her sister Ida fled the persecution of Jews in their native Germany and sought refuge with Bernard. After learning this news in June 1939, Hanna’s brother-in-law Lodewyk Hymans wrote from San Francisco, "Too bad that [Ida] lost all of her money and jewels, at her age she may be lucky that she is in a free country, and with a few relatives around her who still care for her."

Yet even as Lodewyk was describing the Netherlands as a “free country,” he was also sending increasingly urgent pleas to leave Europe while there was still time. On April 20, 1940, Hanna and Jacques left Rotterdam for San Francisco with their two very young sons Herbert and Jacques—Bernard’s grandsons. It must have been hard for Bernard to see them go; a family letter from March 1940 describes him as “altyd opgewekt en bly zyn kinderen en kleinkinderen om zich te hebben” (“always cheerful and happy to have his children and grandchildren around”).

Communications became difficult after the Germans occupied the Netherlands in May 1940, but the California-based Hijmans/Hymans were still able occasionally to receive word from their older brother Siegfried (“Sieg”) Hijmans, who had stayed behind. Several of Sieg’s messages also included updates about Bernard and Ida.

In December 1942, Sieg wrote that his family of five was "alright" and "Also Ida, Bernard."

In February 1943, Sieg wrote that his family was "still together in good health also Ida Bernard."

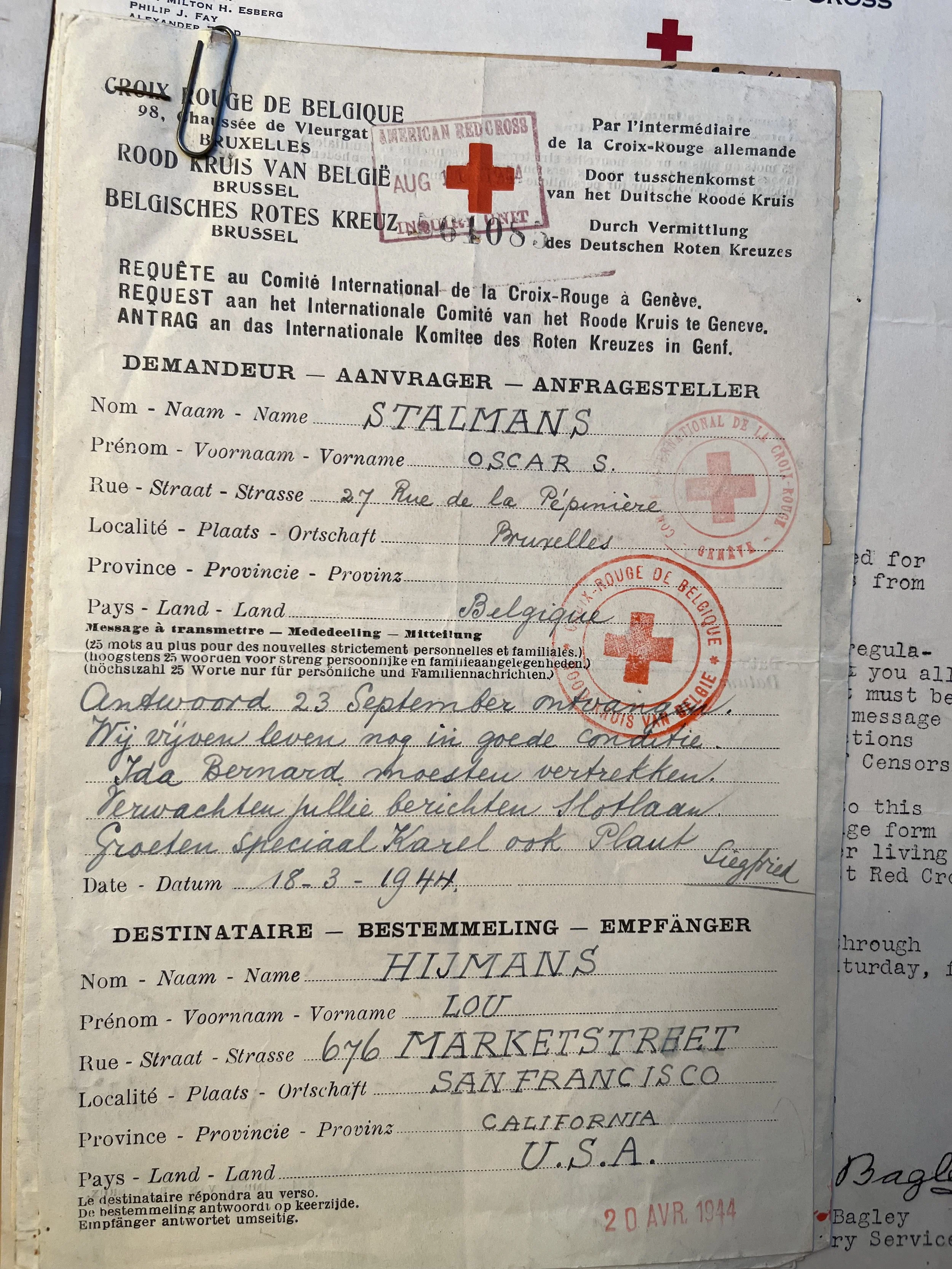

Then in March 1944, Sieg wrote from Brussels under an assumed name, “Oscar S. Stalmans”: “Vij vijven leven nog in goede condition. Ida Bernard moesten vertrekken.” (We are living still in good condition. Ida Bernard had to leave.”)

The March 1944 message is pictured below.

Thus, as of 1944 the family in California implicitly understood the tragic fate of Bernard and Ida, though not yet the precise fact that both had perished at the Sobibor death camp in mid-1943.

Despite becoming a naturalized American citizen and putting down firm roots in California over the subsequent decades, Hanna evidently felt attached to her family home in Haarlem and held on to it until 1974.

As the lone surviving descendant of Bernard Citroen, I am deeply grateful to the City of Haarlem, not only for commemorating his murder at the hands of the Nazi regime, but also for reviving my family’s connection to this little plot of earth.

Jacques Edson Citroen Hymans